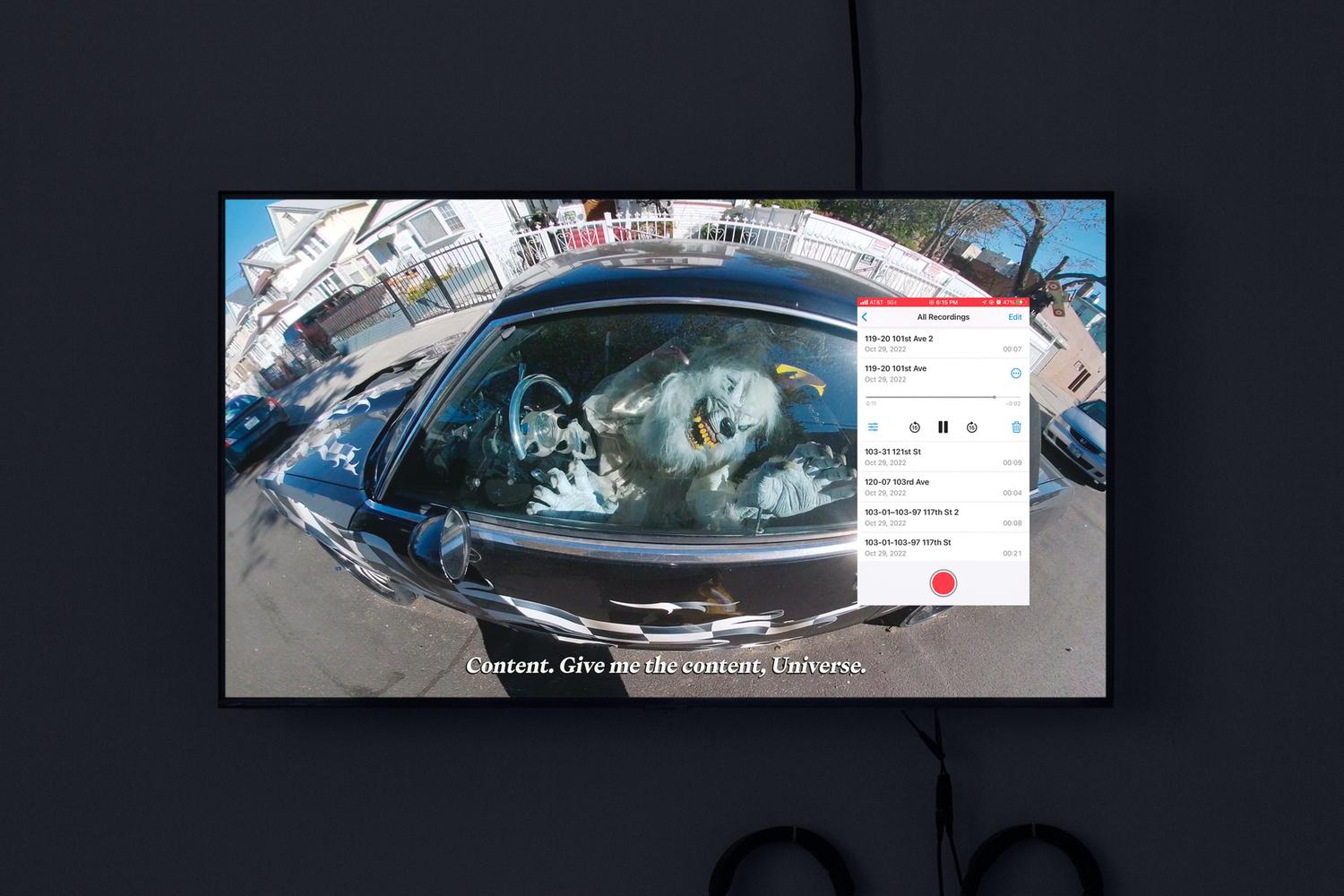

Give me that fucking content, Universe. 2023

single channel video, r/t 1:53,

I spent my first days in New York in October 2017 wande- ring South Asian enclaves in the outer boroughs, hoping to visit neighborhoods similar to Kingsbury, where my grand- mother lives in North West London; for me, locating myself in a diaspora was a sort of stopgap against a creeping sense of post-college abeyance and formlessness. I spent an hour and fifteen minutes on the trains without an exact desti- nation. The homes were decorated for Halloween, when private residences acknowledge the slim commons of the sidewalk and preen for it. The goblins, ghouls, zombies, dismembered figures, skeletons, black cats, ghosts, spiders, spiderwebs, jack-o-lanterns, witches, pumpkins, today remind me that Indian religious art was first received in

the West as depicting demons, as described in art historian Partha Mitter’s book Much Maligned Monsters. Hegel, in his Lectures on the Philosophy of History, said that these artworks betrayed a somatic form of consciousness: the In- dian is “lost in a dream,” sees god everywhere, and through this ubiquity, quote “the Divine is thereby made bizarre, confused, and ridiculous ... degraded to vulgarity and senselessness.” For Hegel, Indian art depicts not monsters, but funhouse gods of a culture stuck in a hallucinatory reverie that can’t really impose cogent categories to divi- de up reality, instead smearing everything together into a single divine substance: “Sun, Moon, Stars, the Ganges, the Indus, Beasts, Flowers — everything is a God.” The fact of cultural difference posed a challenge to Hegel’s integra- tive system, stretched it to its limit, at which he resorted to caricature. However his failure is also a success: projected onto the Hindoo is something that would later be affirmed by psychoanalysis: that fantasies aren’t discrete from wa- king life, but are threaded into our relationships with each other and the world. In the past, I’ve described my haptic interventions into video sequences—augmenting, rotosco- ping, re-scoring, and compositing them—as an attempt to amplify, coax out, or herald the social abstractions, discou- rse, unconscious thought, and discarded sense data that are invisible and overlay our world.

And yet, sometimes I find the world already augmented as was the case with these houses outfitted with memento mori. I found the whole situation funny, a day trip daydream spent seeking capital-C Culture only to find capital-S Spirit. Later, a friend introduced me to Cameron Jamie’s photo book Front Lawn Funerals and Cemeteries, in which the artist took flights from Paris to LA in the mid 80s to take silver gelatin photographs of what he called “The American Grand Guignol,” and I related to his humo- rous, somewhat anthropological presentation of the holiday. A year later, in 2018, I returned with a helmet camera rig I fashioned out of a plasti-dipped motorcycle helmet, a tripod head, and a 360 ̊ action cam, and shot the opening sequence of Mourning in advance (2019), in which a camera rotates on a digital turntable, momentarily pausing on my face, and the houses at which I’m nervously staring. This video en- ded up establishing some coordinates within which I’m still working today: most of my work comes from traversing the city and happening upon scenes that crystallize broader dynamics, in this case, the soft horror of everyday life.

Five years later, upon returning to New York from London, where I completed my MA, I had an inkling to revisit this sequence and make a sequel. In part, it was a way to let go of the pressure to always come up with something novel, and experiment with working serially. However, a lot had changed in that interval, namely, life had become much more difficult and painful, and now for the most part, the decorations now struck me as generic and empty. The work that came from those shoots Give me that fucking content, exemplifies this shift: a manic, panicked, searching mecha- nical gaze frenetically scans the surrounding environment while the titular phrase is repeated with increasing derange- ment in voice notes I recorded between shots. Banal street scenes are rendered ravaged, spiky, saturated with aggressi- ve emptiness, and a demand balloons into a threat.

Vijay Masharani

2024