25.04.2025 - 04.06.2025

Jakob Francisco

Lea Klemisch

Marina Köstel

Malte Möller

Johannes Schwalm

Timon Sioulvegas

Lena Stewens

We are pleased to invite you to the second instalment of the curatorial exchange between Magma Maria (DE) and Salon 75.

Following Salon 75’s exhibition at Magma Maria in Offenbach last autumn, this spring marks the reciprocal chapter: Magma Maria travels to Copenhagen to curate and present a new exhibition at Salon 75.

The exhibition considers mythology not as a fixed narrative but as mutable ground—creating second natures, foundational fictions, and unstable truths. Referencing Land & History, the title gestures toward open-ended mythologies: fluid, layered, obscured and seemingly always open to reinterpretation. Magma Maria is an artist and curatorial collective. From 2020-2024 they ran an exhibition space at Hafenplatz in Offenbach am Main, Germany, with an experimental and collaborative approach, hosting exhibitions, installations, and projects that often explore themes of spatiality, narrative, and materiality.

01.03.25 — 31.03.25

Quay Quinn Wolf

002, 2024

plastic jugs, white roses, water

Emma Hummerhielm Carlén & Jochen Lempert

Curated by Christine Dahlerup for Salon 75

15.12.2024 - 01.02.2025

Housed in a storefront, the architecture of Salon 75 carries traces of its former life as a shop. It is easy to imagine how merchandise was once displayed in the bay window, catching the attention of passersby. Inside, the room is framed by peculiar wall molding with recessed, tilt spotlights that may have been used to direct the gaze onto different objects. In the duo exhibition b/w, the delicate placement of Emma Carlén’s sculptural works and Jochen Lempert’s photographs alternately foreground or divert the circumstances of the space.

Carlén’s sculptural installations turn the logic of display inside out. Upon arrival, one encounters the back of Tilted slabs (2024), a large frame that leans against the window, supported by four cast miniature stools. The slab partly obstructs the view of what is inside the exhibition space. From the outside, passersby can only glimpse how the image surface – a paper sheet – neatly folds upon itself, becoming its own frame. Once inside, the front reveals itself as a blank image plane akin to a projection surface wherein the gaze can wander, and afterimages can appear. Elsewhere, on a table, Spots (2024) float in space like a dozen eyes removed from their sockets, glancing back at the ceiling. Above the bay window, another blank image plane, Untitled (2024), draws attention to a cavity in the room that might have passed unnoticed.

Where the installation of Carlén’s sculptures frames the space, Lempert’s distinctively frameless, black-and-white silver prints are mounted directly onto the wall. Yet their framelessness seems to emphasize that a photograph is already, in itself, an act of framing. It cuts and crops in the field of perception. As the walls of the exhibition space become a temporary frame for the photographs and photograms, formal aspects of the motives begin to converse with the texture of the hosting walls and pick up formal qualities of the space. Miniscule mussels captured on the light-sensitive sheet in Shells (photogram) (2024) evoke the feel of the carpet – or the other way around. A dove, Martha (2005), seems to mediate between the exhibition space and her chosen habitat in the city street. In another frame, a snail thrones on a packet of cigarettes. The white whorl shines in the darker landscape, adding yet another spotlight to the room.

If Lempert, a biologist by training, typically directs his lens at flora and fauna, the exhibition b/w foregrounds other aspects of his oeuvre through photographs that engage with a more abstract and sculptural syntax. The critic laughs (2024) – a mini print that invites a closer, more intimate view – makes familiar parts of the human body appear as four serial sculptures, not unlike Carlén’s cast sculptures of mini stools. The dialogue between the two artists’ practices is not only one of different modes of framing. It is also a conversation between casting and photography as distinct ways of capturing fleeting moments and the shape and textures of things in the world.

- Johanna Thorell

Photos by: Wassily Walter

Chambers, 2022

Silkscreen ink on packaging boxes

Chambers are accumulations of abandoned packaging cases. Minimalist hieroglyphs that have been veiled in monochrome. This transformation brings a new focus to the scene. Michel’s interest lies in the interstices and transitional processes in a world of goods. Gaps as capacities, where he locates the fact that not only material objects but also bodies, desires, and relations are part of a valorising system and are fetishised in their supposed uniqueness.

25.10.24 — 10.12.24

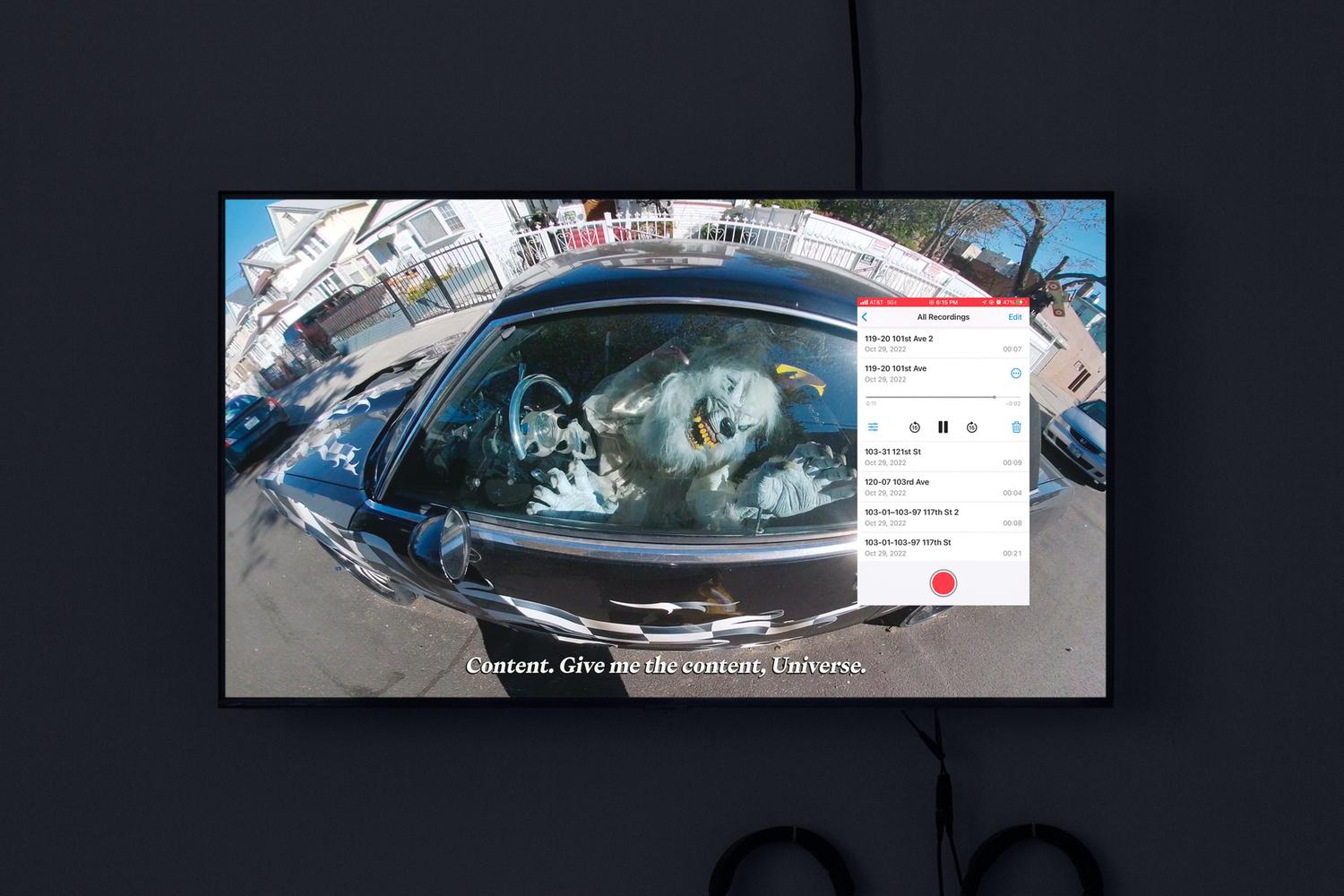

Give me that fucking content, Universe. 2023

single channel video, r/t 1:53,

I spent my first days in New York in October 2017 wande- ring South Asian enclaves in the outer boroughs, hoping to visit neighborhoods similar to Kingsbury, where my grand- mother lives in North West London; for me, locating myself in a diaspora was a sort of stopgap against a creeping sense of post-college abeyance and formlessness. I spent an hour and fifteen minutes on the trains without an exact desti- nation. The homes were decorated for Halloween, when private residences acknowledge the slim commons of the sidewalk and preen for it. The goblins, ghouls, zombies, dismembered figures, skeletons, black cats, ghosts, spiders, spiderwebs, jack-o-lanterns, witches, pumpkins, today remind me that Indian religious art was first received in

the West as depicting demons, as described in art historian Partha Mitter’s book Much Maligned Monsters. Hegel, in his Lectures on the Philosophy of History, said that these artworks betrayed a somatic form of consciousness: the In- dian is “lost in a dream,” sees god everywhere, and through this ubiquity, quote “the Divine is thereby made bizarre, confused, and ridiculous ... degraded to vulgarity and senselessness.” For Hegel, Indian art depicts not monsters, but funhouse gods of a culture stuck in a hallucinatory reverie that can’t really impose cogent categories to divi- de up reality, instead smearing everything together into a single divine substance: “Sun, Moon, Stars, the Ganges, the Indus, Beasts, Flowers — everything is a God.” The fact of cultural difference posed a challenge to Hegel’s integra- tive system, stretched it to its limit, at which he resorted to caricature. However his failure is also a success: projected onto the Hindoo is something that would later be affirmed by psychoanalysis: that fantasies aren’t discrete from wa- king life, but are threaded into our relationships with each other and the world. In the past, I’ve described my haptic interventions into video sequences—augmenting, rotosco- ping, re-scoring, and compositing them—as an attempt to amplify, coax out, or herald the social abstractions, discou- rse, unconscious thought, and discarded sense data that are invisible and overlay our world.

And yet, sometimes I find the world already augmented as was the case with these houses outfitted with memento mori. I found the whole situation funny, a day trip daydream spent seeking capital-C Culture only to find capital-S Spirit. Later, a friend introduced me to Cameron Jamie’s photo book Front Lawn Funerals and Cemeteries, in which the artist took flights from Paris to LA in the mid 80s to take silver gelatin photographs of what he called “The American Grand Guignol,” and I related to his humo- rous, somewhat anthropological presentation of the holiday. A year later, in 2018, I returned with a helmet camera rig I fashioned out of a plasti-dipped motorcycle helmet, a tripod head, and a 360 ̊ action cam, and shot the opening sequence of Mourning in advance (2019), in which a camera rotates on a digital turntable, momentarily pausing on my face, and the houses at which I’m nervously staring. This video en- ded up establishing some coordinates within which I’m still working today: most of my work comes from traversing the city and happening upon scenes that crystallize broader dynamics, in this case, the soft horror of everyday life.

Five years later, upon returning to New York from London, where I completed my MA, I had an inkling to revisit this sequence and make a sequel. In part, it was a way to let go of the pressure to always come up with something novel, and experiment with working serially. However, a lot had changed in that interval, namely, life had become much more difficult and painful, and now for the most part, the decorations now struck me as generic and empty. The work that came from those shoots Give me that fucking content, exemplifies this shift: a manic, panicked, searching mecha- nical gaze frenetically scans the surrounding environment while the titular phrase is repeated with increasing derange- ment in voice notes I recorded between shots. Banal street scenes are rendered ravaged, spiky, saturated with aggressi- ve emptiness, and a demand balloons into a threat.

Vijay Masharani

2024